With the looming winter there just aren’t as many projects to undertake (and to write about), but rather than make yet another video game post I thought I’d ramble a bit about economic and workplace observations. I’m sure that sounds riveting, but I’m not one to mislead with a false premise. If you prefer, simply rename this post’s title to: Ten Things You Need to Know About the Millennial Worforce (in the typical clickbait list fashion).

Although, I still don’t consider myself a Millennial. I fit somewhere into that forgotten Generation-Y group, before Millennials but too young to be a Gen-Xer. And like everyone else, I feel that my generation had it worse, and I will explain why.

I will do so by mentioning two movies that I consider to be flagships of this Lost Generation, Gen-X: Fight Club and Office Space. Media serves as an excellent historical record of a society.

Taken at face value, they’re comedies. Looking deeper, however, I became irritated at the protagonists’ complaints. In Fight Club, for example, a young professional becomes disillusioned with the consumerist society in which he lives, abandons it all, recruits followers, and then uses domestic terrorism to try and topple the financial sector.

Here’s another look: a young professional has more money than he knows what to do with, struggles to find meaning in his life, becomes an asshole at work, foregoes finding a meaningful relationship because he’s a misogynist and opts for a friend with benefits (to whom he’s also an asshole), then creates a gang to commit large-scale vandalism.

In Office Space, a young professional becomes disillusioned with the lack of meaningful employment, struggles with having a relationship, then snarkily finds ways to strike back against his evil corporate overlords. Or, a young professional doesn’t like his job and girlfriend, so he grabs the hottest girl he can find (obvious because it’s Jennifer Aniston–who’s always playing the part of hot chick), shamelessly ceases to do any work (but doesn’t quit his job–just pulls a paycheck while sitting around), then convinces a couple of his colleagues to commit computer crime and steal a lot of money, culminating in some vague message that these actions were maybe not justified, but permissible, since his boss/employer was terrible.

If I extrapolate a line of reasoning akin to the hierarchy of needs, then I would conclude that the Gen-Xers, not having to work as hard for economic sustenance, invented problems, or possibly focused too much on more minor problems, and as a result have a much greater expectation of their effort/reward ratio.

I mention all this because I work with this older generation. As a whole, I’ve been reasonably content in my current role and department, feeling as though I’ve finally achieved a satisfying level of accomplishment and respect (see above: my own cubicle). At least I don’t feel like killing myself anymore, so I was a little surprised that when we took our usual round of company surveys, the overall scores for the department were rather low.

I was not the only one who wanted to know why, as committees were soon formed with the intent of identifying the factors that were lowering the scores. As I was conscripted, I had little say in my involvement. So I just listened. Common complaints were: inconsistencies regarding using benefit time, lack of established policies, perceived lack of trust, and a general feeling of being treated like a child. I found little merit in these claims, seeing them as superficial interpretations of inevitable inconsistencies.

But I suppose the surveys did what they intended: measured the level of employee contentment; and the committees identified specifics. Still, I can’t help but feel that the prior generation had it a little too easy. I suppose, in time, the Millennials will consider me a big whiner with unreasonable demands too.

–Simon

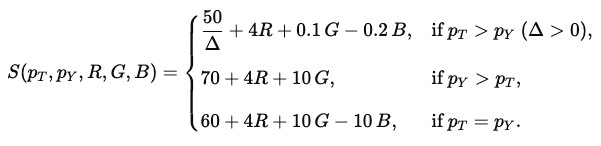

Of course, that nightmarish formula is more readily understood in its natural format: a spreadsheet, so naturally I’ve provided it along with instructions:

Of course, that nightmarish formula is more readily understood in its natural format: a spreadsheet, so naturally I’ve provided it along with instructions: