541 words, 3 minutes read time.

There’s a saying out there something along the lines of: a complex design has a lot of failure points, so it isn’t a good design. Something like that. Of course, sometimes the additional complexity outweighs the detriments. For example, safeties! I very much appreciate that my pistol has dual safeties, because even though their necessity might be low and cause a malfunction, to not have them at all presents potentially lethal consequences.

But this does not apply to all safeties, because the consequences of misuse are not always so extreme. For example, my coffee bean grinder! Am I thankful that the manufacturers took the precautions that prevent me from turning in on and being able to stick my finger into the gears? Um, kind of indifferent there, as that’d be difficult to do even intentionally. But am I annoyed that the spring switch broke inside it and bricked the damn thing? Yes, yes I am. So I opened it (the act of which many designers take pains to prevent, so they can sell me a new product), removed the switch and wired a bypass circuit. Now I can use it again, though I have to be careful to not snake my finger down and around and up inside the extractor chute (again, never a problem to begin with). Bad design!

But the Ninja blender was especially egregious! I always had it in for this thing, because it’s designed to be a smoothie maker primarily, which is fine if that’s all you want to do with it, but the lack of top access prevents other culinary applications, like making emulsions or staging liquid additions. Plus, it’s all made of plastics – yes, the material that makes it possible…to break and have to buy a new unit. Because it’s of course non-user-serviceable (unlike the grinder), and replacement parts are more expensive than the unit!

Specifically, the Ninja is armed with a convoluted safety that stops the blades from spinning if I take off the lid. This alone isn’t a bad idea, since the full-length blade setup needs to be secured by the lid or it’d wobble and fly off across the kitchen. That at least is understandable. What isn’t, however, is everything else I just mentioned. It’s cheap material, the lid keeps breaking, and I can’t buy reasonably-priced parts. The lid activates the safety, so warped lid = no blending.

So at the risk of making a negligent mess or poking out an eye, I again bypassed a safety, because the warped lid still works! I pine for the days before my own when things were actually made to last – a defunct concept gone before I was born. Sigh.

Anyway, here’s what I did, for the archives:

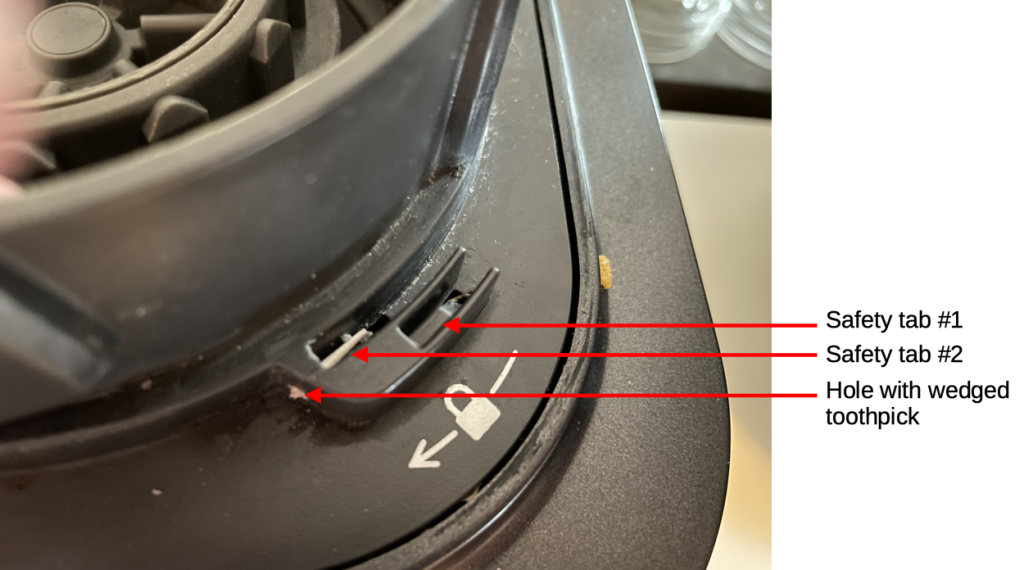

Safety tab #1 determines which modes can be used with which attachments. Whatever.

Safety tab #2 is the universal failsafe. If it’s not depressed, then the unit won’t run. The warped lid failed to depress this sufficiently, so…

I drilled a small hole through which I could insert a toothpick to depress the safety all the way. It’s far enough down that the lid’s safety doesn’t get snagged on it, and I snapped off the excess wood.

And so, anti-consumer hostile design thwarted. Suck it, SharkNinja LLC!

–Simon