As I approach 40, I’m very much aware of my physical decline. But what I didn’t expect was the Internet’s warnings that my overall happiness will apparently be taking a dive soon too. Self-reported subjective measurements make for a lousy scientific statement, so it’s more one of those correlation-only type observations. As to the actual reasoning, that’s up for debate. Common theories include:

- Innocence lost with the realization that your achievement peak has passed and life didn’t turn out that good (insert Pink Floyd song here).

- 40 isn’t quite the point where maximum earning potential is reached, and workload appears imbalanced with quality of life.

- Some form of the above as a midlife crisis.

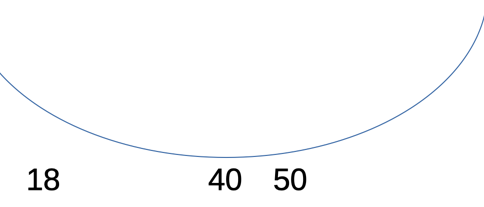

The full graph indicates happiness begins to decline at 18, bottoms out in the 40s, and steadily increases starting at 50. Something like this (this was drawn freehand, so disregard the scaling issues):

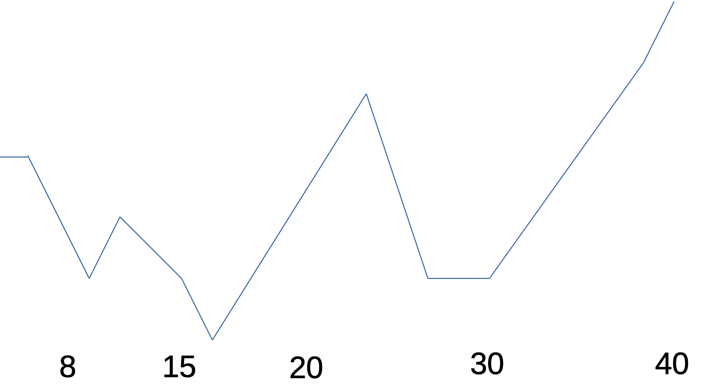

So I decided to compare this timeline with my own life, and see if this is an applicable expectation, using life events as reference:

- 0-7: Limited frame of reference/too young to care. I remember school being okay until we moved.

- 8-11: New school. Kids were jerks. Wasn’t allowed to leave the house. Low happiness.

- 11-12: Junior high started and I really enjoyed the first year.

- 13-15: Struggled with grades. Wasn’t good at extracurriculars. Bad friends. No luck with girls. Low happiness.

- 15-17: Moved across the country. Few friends. Bad grades. No girls. Overbearing parents prevented any kind of social life. No car in a town of rich kids. Bad clothes. Bad hair. No happiness.

- 17-19: Started college. Greater freedom. Discovered interests. Found friends. Increased happiness.

- 19-21: Own apartment. Girlfriends. Finished college. Even more happiness.

- 21-31: Bad grad school experience. Tired of apartments. Horrible jobs and limited opportunities. Wife, car and daughter kept some stability, but overall a period of lower happiness.

- 31-39: Better jobs. More money. Bought a house. Reasonably happy.

- 39-present: Even better jobs and more money. Good life prospects. Happy.

If I try to graph the above, I end up with something like this:

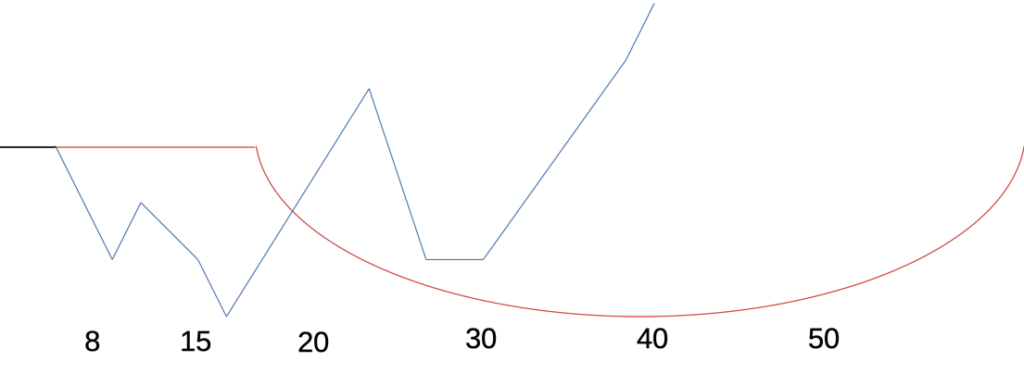

And if I superimpose the two:

It would appear that I’m at the complete opposite level of happiness than where I should be.

Hopefully this means I’m early to the old age happiness party, rather than late to the middle age unhappiness one. Or maybe my life has been atypical in general. Who knows? But what I do know is that right now I’m the happiest I’ve ever been.

–Simon