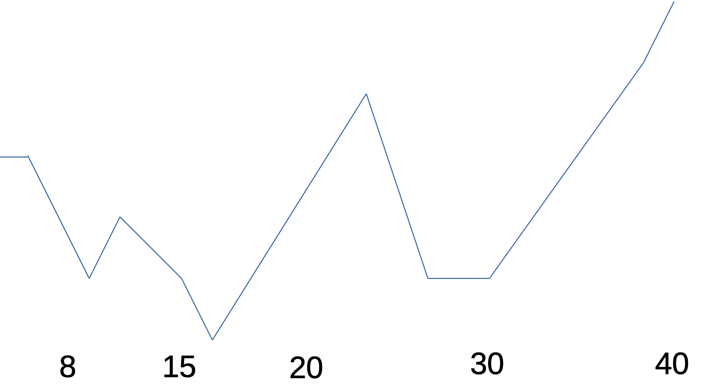

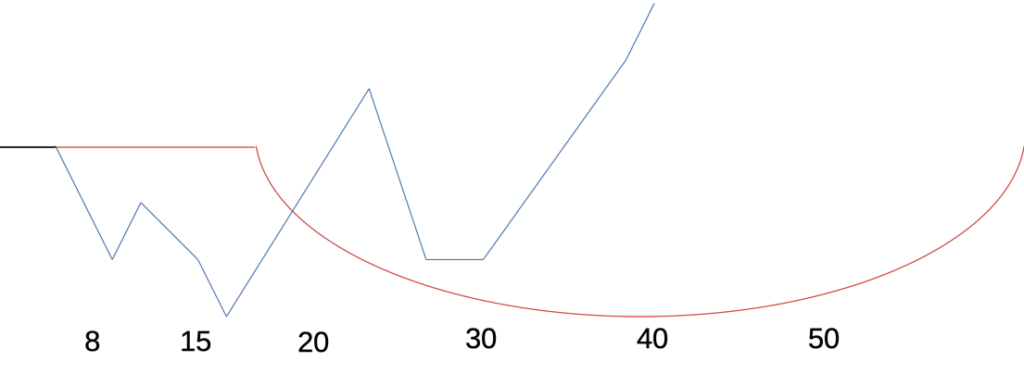

February 23rd marked the 7 year anniversary of this blog, and while I admit that I don’t play the SEO game, I’ll note that it’s remained remarkably hidden for all that time. In fact, without some very pointed key words, I can’t locate it in a search engine. The quickest I was able to find acknowledgment that I exist on the internet was my LinkedIn profile, which was 14th in the search results list for my name (there’s a British banker and a film director who always take the spotlight).

Part of the reason for this shadowed existence I believe is due to me migrating to paid hosting. Ephemerality.net previously redirected to moorheadfamily.net, which is my own hosted domain. And if I search along those avenues, I can find a hit for my personal server there. #20 in the search engine in fact. The landing page is a simple menu I coded, intended to make an easy directory to my site’s main functions.

But there’s more to it than that. I used to always appear on page one, and that was when I had a lot less content.

The real reason I exist in obscurity? Indifference and obsolescence. The world simply just doesn’t care about most of what’s out there, especially if it’s not curated and fed into a standardized format. Gone are the days of old school blogging, superseded by social media. As a holdout (I started my first self-hosted blog on a repurposed G3 Powermac running SUSE Linux in 2007: intellectualnexus.net (prior to that I ran a blog on my iMac via Apache and gave out my IP address)), I can personally vouch for how difficult it is to discover other non-monetized personal blogs. They just don’t appear high up in search results. I can’t even get my parents and siblings to visit my blog. I’ve even sent people links to my site where I’ve posted a recipe – my own recipe – that they asked me for, but analytics never show that the post was ever accessed externally. People just won’t visit blogs, even for the content they want.

The upside is that I don’t have coworkers compiling dossiers of my content that they find offensive in order to get me fired (no really – I’ve been summoned to Human Resources for the most benign of complaints (something that mysteriously ceased once I became permanently remote)). The downside is that blogging seems pointless without an audience. (Hence this site’s mission statement.)

But blogs fill the niche between professional journalism and tweets. And when the tweets die a day later, never to be read again, what is left to chronicle our moment in time, honestly and devoid of bias (financial incentives)?

And so I lament.

–Simon